In 2024, I read 37 books and nearly 16,000 pages.

I keep my book diet varied: some fiction and some non-fiction. Different genres, topics, and authors.

However, one area I had been missing until recently was old books.

I’d seen advice on reading old books on the internet for some time, but I hadn’t gotten around to giving it a try until this year. My personal foray into old business books began with Men and Rubber by Harvey Firestone, the founder of Firestone Tires. The book was written in 1926 and describes the founding, growth, and growing pains of the business.

What I found most interesting were the parallels to the advice of today’s business titans. Abstracted from the context of 1926, Firestone’s advice mirrors what I hear from Musk, Bezos, and others in the 21st century.

Here are a few examples.

Hire missionaries

Passionate people build better products. That’s why founder-led companies are special: they care more than anyone else.

Jeff Bezos coined the “missionary versus mercenary” phrase that describes the importance of having passion for your mission.

“Is that person a missionary or a mercenary?” Bezos says. “The mercenaries are trying to flip their stock. The missionaries love their product or their service and love their customers and are trying to build a great service. By the way, the great paradox here is that it’s usually the missionaries who make more money.”

Turns out, almost a hundred years earlier, Firestone said something similar.

If you ask yourself why you are in business and can find no answer other than “I want to make money,” you will save money by getting out of business and going to work for someone, for you are in business without sufficient reason. A business which exists without a reason is due for an early death.”

Do things that don’t scale

Startups have the advantage of doing things that don’t scale.

This has become widely accepted startup advice, though its implementation will vary for every company. It could be an approach to recruiting, product development or, my personal favorite, a scrappy sales tactic.

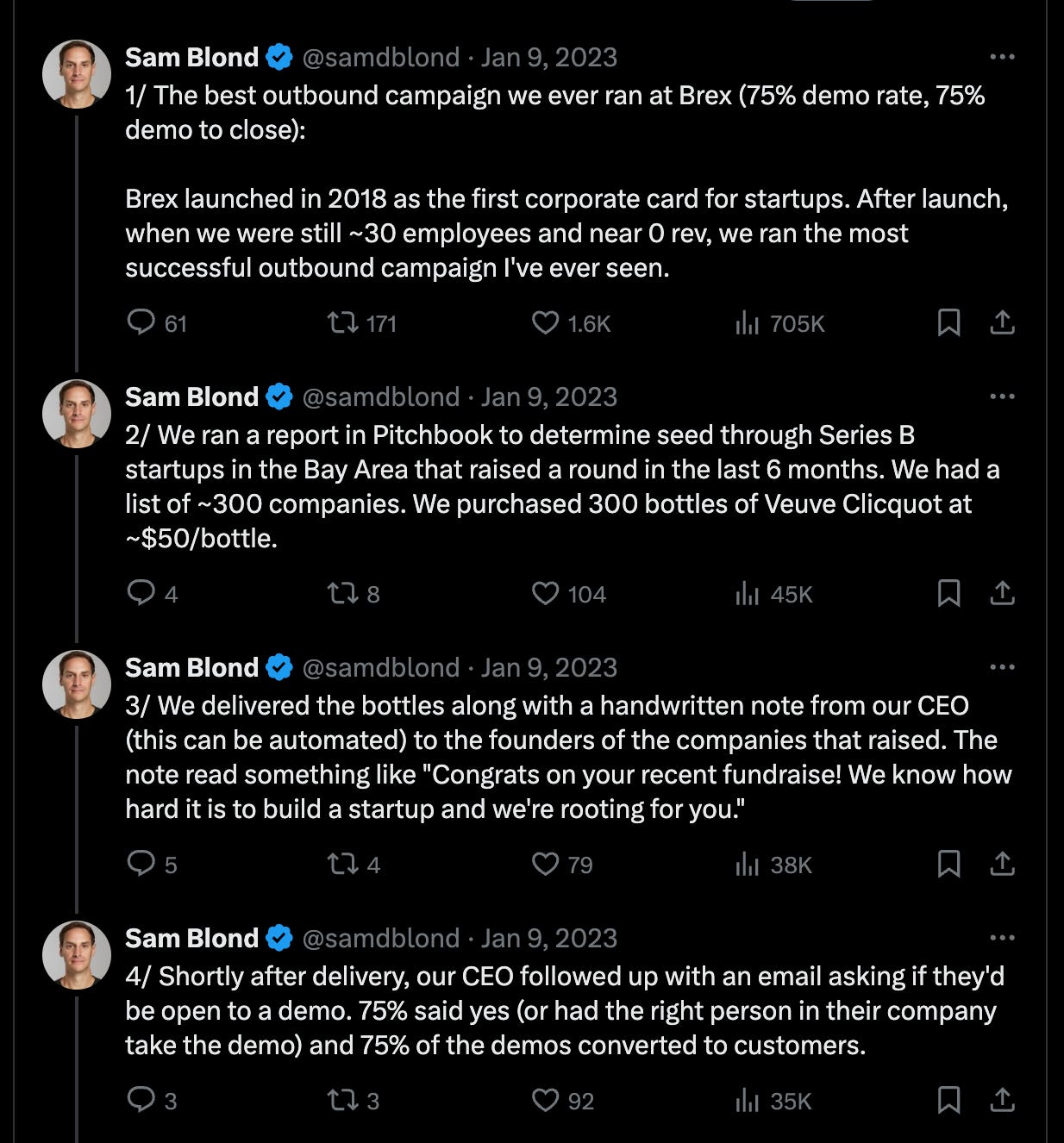

A recent favorite comes from Brex, who sent Champagne to companies that recently raised venture funding.

Firestone had his own version of doing things that don’t scale in sales.

The one man in particular to whom I wanted to sell I could not reach, and that was Will Christy….The trouble was I could not get to him. He had a big office and secretaries and all the usual safeguards of a busy man, and I could not get past those guards. ….I kept tab on Will Christy’s plans, and I learned that he was going to California with his wife for a vacation of several months. I found that he was going to stop over at the Auditorium Hotel in Chicago on his way out, and I took a train ahead of his to Chicago, registered at the hotel, made certain that Mr. and Mrs. Christy had registered later in the evening, and made equally certain that they did not see me that evening, for I already knew Mr. Christy slightly. The next morning I was up very early and kept out of sight until I saw Mr. and Mrs. Christy going in for breakfast. Quite by accident, of course, I met them at the door of the dining room. We had breakfast together. He inquired about our business. One thing led naturally to another, and before breakfast was over he had bought $10,000 worth of stock”

Question everything

One of my favorite Elon Musk interviews outlines his 5 step process for process improvement.

It starts with a simple rule: “make the requirements less dumb”

Harvey Firestone had a similar philosophy: Always ask “Is it necessary?”

“The first question I always ask myself when looking at any operation—whether in the shops or in the office—is this: Is it necessary? Very often it is not necessary at all, but merely a tradition. For instance, it was a tradition that rubber had to age in the warehouse a long time before it could be used. Rubber is expensive and aging cost a lot of money—for we had to keep a deal of money in idle rubber. Everyone told me that this aging was absolutely necessary, but no one could tell me why it was necessary. I suggested that we try going ahead without aging and see what happened. We did go ahead—and nothing happened. The tires stood up just as well as they ever had, and we saved millions. Someone back in the past must have laid down the rule that rubber had to age, and everyone else had followed without question.”

Founder mode

Paul Graham’s Founder Mode essay went viral this Fall. In it, he described how Brian Chesky rejected the conventional wisdom of running a company, which was to delegate more responsibility down the org chart with scale. Ultimately, in Brian’s case, this broke and he had to “invent” this new management philosophy that PG calls “Founder Mode.”

The way managers are taught to run companies seems to be like modular design in the sense that you treat subtrees of the org chart as black boxes. You tell your direct reports what to do, and it's up to them to figure out how. But you don't get involved in the details of what they do. That would be micromanaging them, which is bad.

Hire good people and give them room to do their jobs. Sounds great when it's described that way, doesn't it? Except in practice, judging from the report of founder after founder, what this often turns out to mean is: hire professional fakers and let them drive the company into the ground.

A century earlier, Firestone Tires operated with a similar philosophy:

But the really big problem was management. The business was already too large for me to look after alone, and yet I did not believe and never have believed in what is called “delegation.” I hold that, if anything in the business is wrong, the fault is squarely with management. If the tires are not made right, if the workmen are unhappy, if the sales are not what they ought to be, the fault is not with the man who is actually doing the job, but with the men above him and the men above them, so that, finally, the fault is mine. That is my conception of business.

Power is the universal primitive

With the rapid growth of AI, everyone is talking about data centers. Upstream of those data centers is electricity.

This has caused many tech companies to be concerned with energy generation. Microsoft is reopening a nuclear plant to power their data centers. Crusoe brings computing resources to the source of energy - whether it’s natural gas flares or renewables. Sam Altman claims the future of AI depends on an energy breakthrough. He’s also invested heavily, funding fusion power startup Helion.

Suddenly, everyone cares about energy.

Old books, like Men and Rubber, teach us that this isn’t a new phenomenon. In the 1920s, Henry Ford was as power obsessed as the CEOs of Microsoft or OpenAI today.

While nuclear power was a thing of science fiction at the time, hydroelectric power was not. Henry Ford allegedly couldn’t even pass a stream without “getting out to measure the force” to see if the power could be used.

The Government had built a dam across the Hudson for some war purpose, and Mr. Ford, rather than see the power go to waste, had leased the rights. He intended to put up a tractor plant-or, at least, he thought he might. But his principal reason for leasing was to avoid seeing so much potential power going to waste. He leased a government war dam on the Mississippi for the same purpose, and preventing waste was behind the offer which he made for Muscle Shoals—and which offer he withdrew. Where another man will build a factory and then plan to erect a power station, Mr. Ford will take the power first in the complete certainty that he can find a use for it. With him everything gets back to power. He thinks of his automobiles in terms of power. Mr. Edison and he would dam every suitable stream in the country just to get the power. I doubt if, on our trips, we ever passed an abandoned mill without Mr. Edison and Mr. Ford getting out to measure the force of the stream, inspect the old wheel, and talk about ways and means of putting the waste power to work.

—

You should read more good books

One of the highest ROI changes to my life is reading more books, specifically more good books.

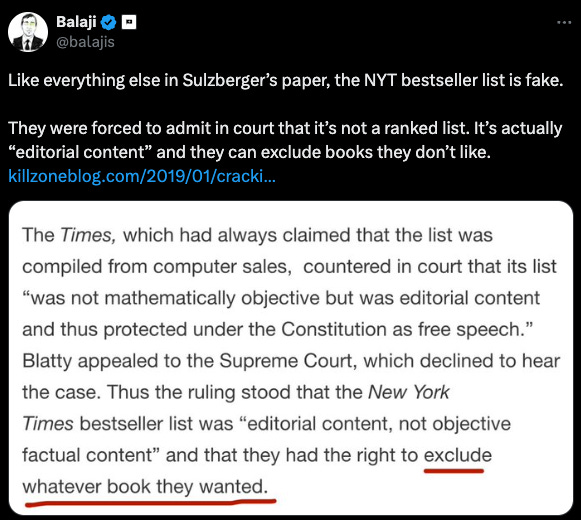

There’s a lot of garbage on the NYT best seller list, which makes sense because it’s not actually a best seller list…

If you read a book that has remained popular over the years, there’s a higher chance it’ll be a good one. And, if the wisdom in those books has persisted, it’s probably pretty good advice.

The quality of information you take in is directly proportional to the quality of your thinking. So, be very careful what you consume.

Have a favorite old books? Comment below!